In a Small Family Business, the Most Important Support Group Is the Family.

The purpose of this special issue is to examine the intersection of entrepreneurship and family business, and more than specifically the notion of the entrepreneuring family. Despite a growing awareness of family-owned businesses and their contribution to the world's developed and developing economies, the contend continues regarding their office in entrepreneurship. Family unit firms are commonly perceived as traditional, erstwhile-fashioned and brackish. The term "family management" has been contrasted with "professional management." Early on family unit business firm enquiry put family and business objectives at opposite poles—as family first versus business beginning (Ward 1997). A more contempo model proposes that business organization-owning families characterized by a potent family orientation (due east.g., interdependence, security, stability, tradition and loyalty) may create a tension that actually pulls the business (and the business-owning family) away from an entrepreneurial orientation (due east.thousand., autonomy, risk-taking propensity, innovativeness, proactiveness, etc.; Martin et al. 2006). Such enquiry enforces the public and academic perception of the entrepreneuring family every bit an oxymoron—that is, a contradiction in terms. However, recent empirical research by Leenders and Waarts (2003) supports an alternative prototype, i.e., a view that strong family and entrepreneurial objectives can role adjacent with one some other (Lumpkin et al. 2008).

Based on the papers presented in this special issue, nosotros argue that it is time to explore this new paradigm more fully, i.e., one that reflects the entrepreneurial behaviors of many family-owned and/or -managed firms. We desire to discover why some concern-owning families embrace dynasty building through innovative beliefs while others reject growth and perform less well than their nonfamily counterparts (Daily and Dollinger 1992; Miller et al. 2008; Upton et al. 2001). What are the effects of family buying on entrepreneurship? More specifically, the papers in this special issue examine 1 or more of the following inquiry questions:

- (1)

What is the effect of family ownership (if any) on various entrepreneurship characteristics?

- (2)

Given family ownership, what other weather condition are probable to stimulate (or hamper) entrepreneurship in the family-endemic firm? And

- (3)

Given family buying, what is the effect of unlike entrepreneurship characteristics on firm (and/or business-owning family) functioning?

Before we discuss the papers in more than detail, we would similar express our pride in presenting the first special issue related to the International Family Enterprise Research Association (ifera) conference that is published in Small Business Economic science Journal and that continues the tradition of the ifera conference to publish special problems in renowned journals (e.chiliad., Klein and Kellermanns 2008). We would like to admit the back up of the ifera and Nyenrode Business Universiteit for sponsoring the research conference in 2008, likewise as the support of Prof. David Audretsch, the editor-in-chief of the Pocket-size Business organization Economics Journal. Most importantly, yet, we would similar to thank the reviewers and authors without whom this special issue would not have been possible.

In the remainder of this introductory commodity, nosotros first clarify the primal terms used throughout this special upshot, including entrepreneurship, family business and the entrepreneuring family. Second, we summarize the key articles and their findings, including their contribution to the broader entrepreneurship and management literatures. Tertiary, we propose a framework based on these results, and finally we offer directions for future inquiry.

Definitions of entrepreneurship, the entrepreneuring family and the family unit business

Co-ordinate to the Austrian School of economic idea, the essence of entrepreneurship is the pursuit of increasing the value of a concern'south avails by seeking out and/or creating new business opportunities (Gartner 1990; Hoy and Verser 1994; Republic of ireland et al. 2001; Kirzner 1997; Wright 2001). 4 of the papers in this issue (Cruz and Nordqvist this issue; Zahra this upshot; Zellweger and Siegel this issue; Kellermanns et al. this result) differentiate family firms based 1 or more components of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). Sciascia et al. (this upshot) focus more specifically on international entrepreneurship, that is, the "discovery, enactment, evaluation and exploitation of opportunities across the national border to create futurity appurtenances and services" (Oviatt and McDougall 2005, p. 540). Finally, Berent-Braun and Uhlaner (this issue) focus on the entrepreneurial motives of the business concern-owning family as the decision to grow or not to abound. In dissimilarity to these half-dozen papers, a seventh newspaper, by Chlosta et al. (this result), focusing on the individual level of analysis, defines entrepreneurship equally the career pick of self-employment.

Entrepreneuring families, furthermore, refer to that subset of business concern-owning families focused on entrepreneurial objectives or motives. Past focusing on entrepreneuring families, we recognize that some (though not all) groups of family owners work together to abound family unit wealth by way of business value cosmos (encounter Berent-Braun and Uhlaner this issue).

Regarding the definition of family unit business, the papers in this special issue vary considerably in their operational definition of family unit business, every bit well as whether nonfamily firms are included in the overall sample. Some studies require merely that a business meets the criterion that a majority (more than l%) of ownership is in the easily of one family (e.g., Cruz and Nordqvist this consequence; Zellweger and Siegel this issue; Zahra this issue). Others add a requirement that companies describe themselves as a family unit business (Sciascia et al. this result; Kellermans et al. issue). Comparisons in results across articles thus must be considered carefully given such differences. Just one report in the special issue, furthermore, samples both family unit and nonfamily firms to compare differences between the 2 groups (Zahra this issue).

Overview of the articles in the special event

One of the goals of this special issue is to examine the interface of entrepreneurship and family unit business organisation from different angles to recognize entrepreneuring families. A wide range of theories is represented in the different articles. These theories are borrowed from the fields of economics, management and other areas of social sciences including psychology and sociology. Specifically, some articles describe on bureau, stewardship and stagnation perspectives. Others utilize the behavioral theory of the house, and draw on the literature of social capital, team building, social learning and personality research. Tabular array 1 provides a brief synopsis of the papers including an overview of sample size, country of data collection, choice criteria for subjects included in the study, the framing of the entrepreneurship-related constructs and a brief summary of key findings. In describing the papers in this special issue, we also highlight their contributions to the broader literatures in management and entrepreneurship.

Sciascia and colleagues (this issue) aim to resolve conflicting research findings on the internationalization of family unit firms by testing the relationship between family ownership and intensity of international entrepreneurship. Specifically, they examine the relationship between the per centum of disinterestedness held past the owning family and the proportion of total sales that are foreign, building alternative predictions based on the stewardship and stagnation perspectives. Results from one,035 US companies signal a nonlinear (inverted u-shaped bend) relationship between ownership and performance. They interpret their findings to suggest that a stewardship upshot is most prevalent for moderate levels of ownership (in their sample 53%). They fence that beyond optimal levels of family unit ownership a stagnation effect develops due to conflict and chance aversion. Thus, this paper highlights how family ownership affects international entrepreneurship. It also points more mostly to the value of because potential curvilinear effects of buying structure on house-level outcomes.

The key purpose of the study by Cruz and Nordqvist (this outcome) is to run into whether generation moderates the effects of ecology factors and company predictors on EO. Their study is based on 882 Spanish small-scale and midsized companies. Their results bespeak that generation serves as a cardinal contingency variable. Most notably, their strongest finding suggests that the impact of nonfamily managers and nonfamily investors on EO is well-nigh apparent in the third generation and later. Effects of ecology variables, including industry growth, technological opportunities, and environmental dynamism, on EO are strongest in the second generation. Based on these empirical results, this study emphasizes the need to consider the generation of the family house when determining how best to encourage entrepreneurship. Information technology also suggests the importance of considering the effects of ecology factors on EO not only for family firms but also for firms more more often than not.

The purpose of the study by Zahra (this issue) is to identify determinants of organizational learning on EO. Thus, organizational learning is used both equally a dependent variable and as a mediating variable to predict EO. Data were gathered via a post survey targeting the fifty biggest and 50 smallest US manufacturers in 40 different industries, resulting in 741 usable cases. Applying the behavioral theory of the firm, results prove a positive human relationship between family ownership and breadth and speed of organizational learning. Zahra's results ostend the prediction that managers who accept an incentive, such as an ownership stake, are more likely to engage in organizational learning. He as well finds a positive interaction effect between family ownership and cohesiveness in predicting breadth and speed of organizational learning. Additionally, his findings show that the breadth and depth of organizational learning and the interaction between cohesiveness and ownership positively contribute to a family firm's EO. This newspaper contributes to the literature not merely by exploring antecedents and consequences of organizational learning, simply also past highlighting the demand to consider different dimensions or aspects of organizational learning (i.eastward., breadth vs. speed) in management research.

The study by Zellweger and Sieger (this issue) likewise looks at the EO of family unit firms. It employs qualitative methods to provide a richer understanding of corporate entrepreneurship. The in-depth case studies are drawn from the STEP (Successful Transgenerational Entrepreneurship Practices) project. Three family unit firms from Switzerland are studied via multiple in-depth interviews with family unit and nonfamily members in top echelon positions at each business firm. Publicly bachelor fabric is too used to supplement the information obtained from the interviews. In a novel estimation of EO, Zellweger and Sieger (this issue) split three of the core dimensions—autonomy, innovativeness and risk-taking propensity—into subdimensions to explore their complexities in family firms. Based on ratings by an independent panel of researchers, they then investigate differences among those subdimensions. With the limitations of a pocket-sized sample case study in mind, the results provocatively suggest that success over the long-term does not necessarily crave uniformly high EO across all dimensions. They interpret these findings equally follows: over time, successful family firms may alternate between periods of exploration and exploitation, adopting different company strategies over fourth dimension to maintain their success. This dynamic view of EO may as well exist of value when researching long-lived nonfamily firms.

Cartoon from agency and stewardship theory predictions, Kellermanns et al. (this effect) investigate the human relationship between family influence and firm operation and also examine how innovation moderates this human relationship. The authors test this model on a sample of 70 US firms drawn from two family concern centers. Results prove better performance for family firms that share management control amid several family members in comparing to those where management is centralized in the hands of 1 family member. Furthermore, family unit firms perform better when ownership is concentrated in a single generation versus spread out amid two or more generations. In sum, findings from this study propose that while the sharing of management command is beneficial to family firms, the sharing of ownership across generations may cause problems. Regarding innovation, family firm innovativeness is found to have a positive impact on house performance. Nevertheless innovativeness has the greatest do good for family unit firms with ownership concentrated within one generation. Thus, this study demonstrates the link between innovativeness and performance for family firms but that depending upon the generation of buying, innovativeness benefits some family unit firms more than than others. It also suggests the importance of considering interaction effects of ownership structure and innovation more than generally in determining the impact of innovation on house performance.

Berent-Braun and Uhlaner (this outcome) aim to predict direct and indirect effects of family governance practices on financial performance, every bit measured by both company and family unit nugget operation. They base their hypotheses on organizational social capital theory, viewing shared focus every bit a type of associability, and family governance practices as applications of teambuilding theory. Utilizing 64 cases fatigued from 18 countries, Berent-Braun and Uhlaner demonstrate that a shared focus on growing and preserving family wealth, a key characteristic of the entrepreneuring family, mediates the human relationship between family governance practices and financial performance. Appropriately, their study shows that the family unit's commitment to growth and wealth preservation acts as a machinery through which the family unit works to enhance business firm operation. Although focused on family firms, the paper as well provides directions for future enquiry using (ownership) social capital equally a mediator in predicting the effects of ownership on firm level performance.

The final newspaper by Chlosta et al. (this issue) focuses on the individual entrepreneur, rather than the entrepreneuring family. They investigate whether the parent, as a role model, affects the next generation's decision to pursue cocky-employment. Chlosta et al. (this issue) base their hypotheses on social learning theory and also use personality research to investigate the part of openness in influencing the attractiveness of an entrepreneurial career. Based on 461 side by side generation respondents, results show that children are more likely to pursue self-employment when they accept a paternal role model (i.e., a father who is cocky-employed), and they accept a high degree of openness. Furthermore, they observe a pregnant interaction consequence between the presence of a paternal part model and openness. Interestingly, the findings indicate that individuals with low openness may notwithstanding exist attracted to cocky-employment if a parental role model is present. As such, this paper alludes to the powerful influence a family can have on encouraging entrepreneurship—specifically the pursuit of self-employment.

Understanding the epitome of the entrepreneuring family firm

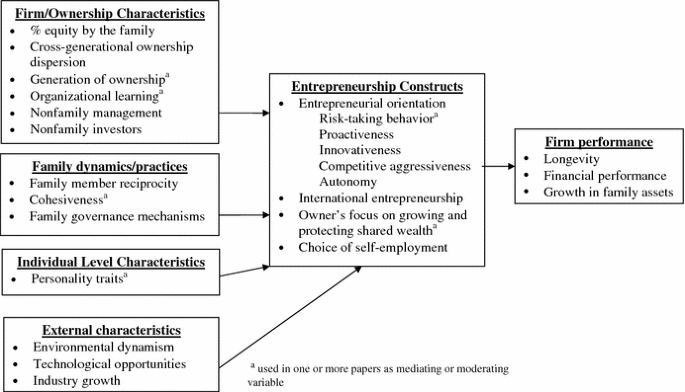

Figure 1 presents a schematic framework of entrepreneurship, family unit business and the entrepreneuring family summarizing the variables in this special issue. Although by no ways an exhaustive list, we offer this figure as a starting point of highly relevant variables for studies of the intersection of entrepreneurship and family buying.

Simplified framework for the special issue on the entrepreneuring family unit

Regarding possible predictors of entrepreneurship, we tin grouping variables according to house/ownership characteristics, family dynamics/practices, individual characteristics (of respondents and/or directors) and external characteristics. The center of the diagram summarizes the cardinal entrepreneurship constructs used in one or more papers. Finally, as tested in some of the papers, the framework implies a direct relationship betwixt one or more than entrepreneurship constructs and either family unit-owning group or firm performance, including longevity, family firm performance and family nugget performance. The framework simplifies the relationships proposed in a number of manufactures. In detail, several variables may exist alternatively used every bit independent, control, mediating or even dependent variables, depending on the item article.

Not shown in the figure are also a number of variables used as controls in one or more studies. These include, for instance, company size, age and sector, past performance, family interest, top direction age and gender, liquidity, research and development spending, high technology industry, life wheel, number of family owners, and finally, degree of overlap of management and ownership.

Fundamental trends based on manufactures in this consequence

This section highlights some of the key trends regarding entrepreneurship in family businesses and business-owning families based on the findings of the papers in this special issue. In particular, we accost those variables that appear to explicate differences in entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurship too every bit functioning differences. We besides summarize findings related to nonlinear effects and address important mediating and moderator variables. Finally, we discuss those theories that seem best supported by the results.

What makes some family unit businesses more than entrepreneurial than others

Several papers in this issue examine factors that explain differences in entrepreneurship, whether or non those same indicators are associated with financial performance on the business firm. These factors range from ownership structure (proportion of disinterestedness of the family unit; whether in that location are nonfamily investors), family dynamic characteristics (cohesiveness, common vision to preserve or growth family unit wealth), family unit governance practices, company characteristics (organizational learning, composition of management-family vs. nonfamily) and characteristics of the manufacture and/or competitors of the house (environmental dynamism, technological opportunity and industry growth). Although most of these variables are found to exist of import predictors, they are not e'er linear in effect, and may exist mediated by other variables. One clear determination across the various studies is the importance of taking factors other than family buying into business relationship when predicting entrepreneurship. A 2nd conclusion is the need to exist sensitive to sampling differences when comparing results. Thus, for instance, with respect to ownership construction, Sciascia et al. (this issue) observe a nonlinear relationship betwixt family ownership and intensity of international entrepreneurship. On the other hand, Zahra'southward findings (Zahra this result) show a positive linear relationship between family ownership and entrepreneurial orientation. Simply differences in results for the ii studies could have several causes, including, for case, differences in sampling (inclusion of singly owned and larger firms in the case of Zahra's research), or the type of dependent variable predicted (EO vs. foreign activity as a percentage of sales).

In summary, making comparisons regarding the prediction of entrepreneurship beyond the studies presented in this issue is somewhat challenging since samples vary widely regarding company size, age, and nature of buying. They also vary in definition and operationalization of entrepreneurship. However, the types of variables examined point to potential directions for futurity inquiry, which volition be discussed in a afterward section.

Entrepreneurship and functioning among family unit firms

Reviewing the iii papers predicting fiscal performance based on entrepreneurial characteristics (Kellermanns et al. this issue; Berent-Braun and Uhlaner this event; Zellweger and Sieger this upshot), results advise that family businesses tin can indeed reflect one or more than entrepreneurial characteristics, and these may help to explain differences in house functioning. However, the conclusion that necessarily all firms that are more innovative, more than proactive, more than autonomous, and more than risk taking is probably an oversimplification, get-go of all because these terms may reflect a variety of subdimensions with rather contradictory meanings, as Zellweger and Sieger (this issue) demonstrate with their qualitative results. The nature of innovativeness (incremental vs. radical or process vs. product) may affair, as might dissimilar types of autonomy (internally, group members acting independently from each other vs. the family unit every bit a grouping acting autonomously from external stakeholders). Future inquiry on entrepreneurship and operation would benefit from taking a more than nuanced and detailed approach thus to the different dimensions of entrepreneurship every bit usually defined.

Theories used to study entrepreneurship in the family business

The central theories covered in the special issue can be grouped into three categories: (1) incentive theories of human beliefs, such equally agency theory and the behavioral theory of the house; (2) social psychological theories dealing with group dynamics, such as organizational social capital, team building and stewardship theory; and (3) social learning theory. These studies contribute to the broader direction and entrepreneurship literatures by providing support for these theories as applied to the topic of the entrepreneuring family.

For instance, Zahra (this upshot) draws on the behavioral theory of the business firm (Cyert and March 1963) in predicting the positive relationship between family ownership and both organizational learning and entrepreneurial orientation. His logic is simple: owners will have a greater incentive to acquire than nonowners. In an application of agency theory Kellermanns et al. (this issue) argue that equally ownership becomes more than complex and resides in multiple generations, the potential for discord and competing interests rises exponentially, with the close personal ties weakening. Regarding family management, the more than family that is involved with management, the greater the overlap of ownership and management, and as a result, the interests of the principals (i.east., owners) and agents (i.e., management) will also overlap and lead to superior results. Results from both studies are consequent with predictions.

Other research in this issue (Sciascia et al. this outcome; Berent-Braun and Uhlaner this issue; Zahra this event; Kellermanns et al. this issue) draws on some aspects of stewardship, team building and/or organizational social majuscule theory. These theories focus on the collective goodwill of the family business firm, and the part that this may play in guiding company strategy and performance. In all these studies, there is an implicit assumption that if family members deed counter to self-interest, firm performance will benefit, which is an underlying supposition in both stewardship and organizational social capital theory (Leana and van Buren 1999).

Social learning theory (Bandura 1986) forms the basis for research past the 1 individual-level study (Chlosta et al. this outcome). Chlosta et al. (this effect) find, in particular, that the paternal (vs. maternal) office model is especially important in influencing self-employment and that this outcome interacts with the personality variable of openness. Nether conditions of loftier openness, the parental part model makes less of a difference. By integrating these two theoretically distinct streams from psychology (personality theory and social learning theory), Chlosta et al. (this issue) better the predictive ability of the model of self-employment beliefs.

Methodological considerations in future research

In addition to the content aspects discussed in the previous section, there are a number of methodological aspects to consider in inquiry on the entrepreneuring family unit. In this section, we accost some of these issues as well as advise directions for future research considering these problems.

Operationalizing the family unit concern

The papers in this issue vary considerably in how they define a family unit business (see Table 1). While this points to the heterogeneity and complexity of family firms, information technology also suggests that hereafter research may want to vary how family unit firms are operationalized when testing their hypotheses to prove the stability of the findings and to demonstrate when they are about applicative (e.k., Chang et al. 2008; Sirmon et al. 2008). The papers also propose that the determinants of entrepreneurship may exist unlike for immature family businesses versus older, larger, or later generation firms (Gersick et al. 1997; Hoy & Sharma 2010). Time to come studies that explore how entrepreneurial elements like exploration and exploitation differentially contribute to the success of family firms depending on factors like age, size and generation may help to explicate the divergent views of family unit firms as either stagnant or entrepreneurial.

A related issue is the importance of differentiating family versus (single-owner) founder effects. This is especially helpful when using indices that measure out proportion of equity owned by one family (which can exist highly correlated with single possessor, first generation firms; see Zahra this result) or other measures of concentrated buying versus dispersion across multiple generations (Kellermanns et al. this issue).

Nonlinear relationships

The studies in this issue focused on a large variety of predictors. Even so, only 1 study (Sciascia et al. this outcome) investigated a non-linear event. Thus, we desire to encourage future research to investigate curvilinear relationships.

Multiple levels of assay

In addition, a multi-level arroyo (for an instance, meet Eddleston et al. 2008) that investigates how firm level variables and individual level variables touch entrepreneurial behavior in family unit firms is warranted. Individual characteristics of the owners are not incorporated into whatsoever of the six papers that predict company characteristics. The type of company that a parent may own (family, later on generation or founder-led) is not used every bit a control in the prediction of individual behavior by Chlosta et al. (this effect). Cantankerous fertilization of psychological, economic and direction variables may provide further explanations for differences in variance at both levels of analysis in time to come research.

Mediating and moderating effects

A third direction in hereafter research relates to the importance of moderating and mediating effects. In the various papers in this special issue, researchers identify several significant moderator effects, including generation (Cruz and Nordqvist this effect), openness (Chlosta et al. this consequence) and family cohesiveness (Zahra this issue) in the prediction of entrepreneurship. Innovativeness also serves as a moderator variable in the prediction of performance (Kellermanns et al. this issue). In the written report by Berent-Braun and Uhlaner (this issue), owner focus on shared wealth significantly mediates the relationship between family governance practices and fiscal performance.

Non all suggested mediating furnishings are tested. Thus, although the newspaper by Sciascia et al. (this issue) presents plausible reasons for the u-shaped curve for family ownership based on such (ownership) social capital variables as trust, reciprocal altruism and trend to build long-term relationships, they exit information technology to futurity researchers to test for these furnishings.

Obtaining multiple observations per firm

Finally, although the fundamental informant approach is widely accepted, it would be helpful, especially for more perceptually based variables such as family trust, delivery, and cohesiveness, to collect data from multiple respondents. In addition, we would similar to encourage the collection of a matched set of information. Such a design would eliminate mutual method bias by utilizing the predictors from one set up of family unit members and utilizing a dependent variable from another family member. Studies that consider the viewpoints of various stakeholders, eastward.g., family unit employees, family owners, nonfamily employees, and customers, would besides contribute to the family house literature.

Conclusions

In conclusion, equally shown in this special event, many family firms certainly comprehend entrepreneurship. While non all family firms are akin with respect to innovativeness, proactiveness, gamble taking, international entrepreneurship or their commitment to pursue firm growth, our collection of papers demonstrates that the stereotype of family firms as resistant to alter, stagnant and myopic is dated. Perhaps family firms should be seen equally silent champions of entrepreneurship, guarding their entrepreneurial secrets from the public eye and many times, not revealing their family unit ties when they are praised for their innovation in the popular press. Surely, this special issue brings the entrepreneurial tendencies of family firms to the forefront and suggests that it is time for a new paradigm, one that reflects the entrepreneurial spirit of many family firms.

References

-

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

-

Berent-Braun, M. M., & Uhlaner, 50. 1000. (this issue). Family unit governance practices and teambuilding: Paradox of the enterprising family. Small Business organisation Economic science Periodical.

-

Chang, E. P. C., Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2008). Regional economy as a determinant of the prevalence of family firms in the The states: A preliminary written report. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32, 559–573.

-

Chlosta, South., Patzelt, H., Klein, Due south. B., & Dormann, C. (this outcome). Parental part models and the decision to get cocky-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Minor Business organisation Economics Journal.

-

Cruz, C., & Nordqvist, M. (this issue). Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: A generational perspective. Minor Business organization Economics Journal.

-

Cyert, R., & March, J. (1963). Behavioral theory of the house. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

-

Daily, C. G., & Dollinger, Chiliad. J. (1992). An empirical examination of ownership structure in family and professionally managed firms. Family Business concern Review, 5(2), 117–136.

-

Eddleston, K., Otondo, R., & Kellermanns, F. Due west. (2008). Conflict, participative decision making, and multi-generational ownership: A multi-level analysis. Journal of Small Business organisation Management, 47(i), 456–484.

-

Gartner, Due west. B. (1990). What are we talking about when we talk about entrepreneurship? Periodical of Business Venturing, 5, 15–28.

-

Gersick, K. E., Davis, J. A., Hampton, 1000. Yard., & Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation: Life cycles of the family business organization. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

-

Hoy, F., & Sharma, P. (2010). Entrepreneurial family unit firms. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

-

Hoy, F., & Verser, T. G. (1994). Emerging concern, emerging field: Entrepreneurship and the family firm. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practise, 19, 9–23.

-

Republic of ireland, D., Hitt, M. A., Army camp, Southward. Chiliad., & Sexton, D. L. (2001). Integrating entrepreneurship and strategic management deportment to create business firm wealth. University of Management Executive, 15, 49–63.

-

Kellermanns, F. W., Eddleston, Yard. A., Sarathy, R., & White potato, F. (this issue). Innovativeness in family unit firms: A family unit influence perspective. Small Business Economics Periodical.

-

Kirzner, I. (1997). Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market place process: An Austrian approach. Journal of Economic Literature, 35, threescore–85.

-

Klein, S. B., & Kellermanns, F. Westward. (2008). Understanding the non-economical motivated behavior in family firms: An introduction. Family unit Business Review, 20(two), 121–125.

-

Leana, C. R., & Van Buren, H. J. (1999). Organizational social capital and employment practices. University of Management Review, 24, 538–555.

-

Leenders, Thousand., & Waarts, E. (2003). Competitiveness and evolution of family unit businesses: The part of family and business orientation. European Management Journal, 21(6), 686–697.

-

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, One thousand. G. (1996). Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking it to Performance. Academy of Direction Review, 21(1), 135–172.

-

Lumpkin, One thousand. T., Martin, Due west., & Vaughn, Yard. (2008). Family orientation: Individual-level influences on family house outcomes. Family Business concern Review, 21(2), 127–138.

-

Martin, West. L., Vaughn, M., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2006). Towards a clarification of "family orientation": An integration of entrepreneurship and family business theories. In S. Zahra et al. (Eds.) Frontiers of entrepreneurship inquiry 2005. Proceedings of the 25th annual entrepreneurship enquiry conference. Babson College: Wellesley, MA.

-

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Scholnick, B. (2008). Stewardship vs. stagnation: An empirical comparison of pocket-size family unit and non-family businesses. Journal of Management Studies, 45(1), 51–78.

-

Oviatt, B. Yard., & McDougall, P. P. (2005). Defining international entrepreneurship and modeling the speed of internationalization. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Do, 29, 537–554.

-

Sciascia, S., Mazzola, P., Astrachan, J. H., & Pieper, T. M. (this issue). The role of family unit ownership in international entrepreneurship: Exploring nonlinear effects. Modest Business concern Economics Periodical.

-

Sirmon, D. Chiliad., Arregle, J.-50., Hitt, M. A., & Webb, J. W. (2008). The function of family unit influence in firms' strategic responses to threat of imitation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Exercise, 32(6), 979–998.

-

Upton, N., Teal, Eastward. J., & Felan, J. T. (2001). Strategic and business planning practices of fast growth family firms. Journal of Minor Business Management, 39(1), 60–72.

-

Ward, J. L. (1997). Keeping the family business healthy: How to plan for continuity growth. Profitability and family unit leadership. Marietta, GA: Business Possessor Resources.

-

Wright, Thou. (2001). Entrepreneurship and wealth cosmos: Sue Birley reflects on creating and growing wealth. An interview past Mike Wright. European Management Periodical, 19, 128–135.

-

Zahra, S. A. (this issue). Organizational learning and entrepreneurship in family firms: Exploring the moderating result of ownership and cohesion. Small Business Economic science Periodical.

-

Zellweger, T., & Sieger, P. (this result). Entrepreneurial orientation in long-lived family firms. Small Business Economics Periodical.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Boosted information

An erratum to this article tin be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9315-x

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Uhlaner, Fifty.Grand., Kellermanns, F.Due west., Eddleston, One thousand.A. et al. The entrepreneuring family unit: a new paradigm for family business organization research. Small Bus Econ 38, 1–11 (2012). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11187-010-9263-10

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9263-10

shortridgeoursend.blogspot.com

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11187-010-9263-x

0 Response to "In a Small Family Business, the Most Important Support Group Is the Family."

Postar um comentário